By Ifra Jan* and Karmanye Thadani**

Introduction

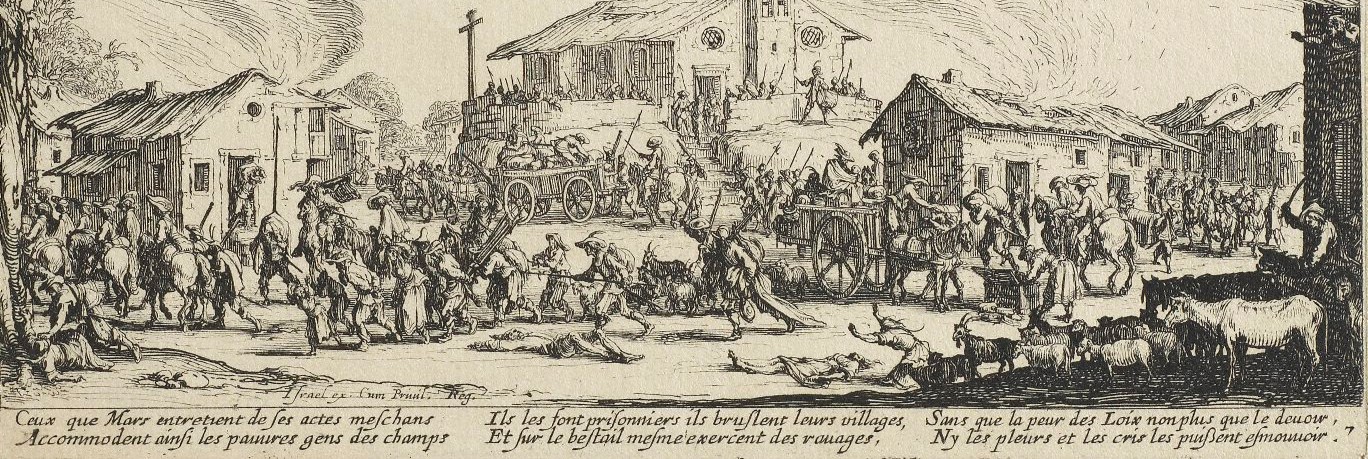

One of the most important driving forces behind the decision to establish the United Nations was the prime determination “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in their life time had brought untold sorrow to mankind”. However, even after the formation of the United Nations, several armed conflicts and wars continue to inflict pain and suffering. In this consideration, the Humans Rights Committee during its sixteenth session in 1984 observed that “war and other acts of mass violence continue to be a scourge of humanity and take the lives of thousands of innocent beings every year”.

Generally, in situations of conflict arising from the territoriality principle, states have the power to take jurisdiction over the crimes committed within their territory, which is inherently defined under their sovereignty. However, under nationality principles, states would assume jurisdiction over the crimes committed by their nationals outside the boundaries. In the exercise of their sovereignty, states can delegate the task of trying a particular type of offence to an international body. This was done after World War II and, more recently, after the conflicts in the Balkans, in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Timor Leste and to a less extent in Cambodia.

Before the inception of the International Criminal Court (ICC), a brief introduction to the two ad hoc tribunals, International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), is important, as this would further highlight the importance of the ICC. Firstly, the United Nations Security Council set these ad hoc tribunals in order to exercise and maintain its security and peace powers which are defined under Chapter VII of the UNSC charter (Action with Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression). Secondly, these tribunals shared their respective jurisdictions with the national courts (like the ICC as well), however, there was no mention anywhere that the decision of the tribunals shall supersede the national courts (unlike the ICC). Lastly, the tribunals only served at a specific location under a special time frame and were subjected to selective justice, which failed to transpire into the world at large, which was facing similar crises during the same time.

The ICC statute was adopted on 17th July 1998, in Rome, on the culminating day of a Diplomatic Conference. 120 states were signatory to the creation of the ICC. However, only 60 countries ratified the Rome Statute in 2002. The Canadian Mennonite University aptly sums up the statute as:

“The Statute establishes the Court as an international body with legal personality. The Statute provides that the Court will have jurisdiction over natural persons in respect of the crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression. It sets out a definition for each of these crimes except aggression. The Court will not exercise jurisdiction in relation to aggression until the States Parties have adopted a provision defining the crime and setting out the conditions under which the Court’s jurisdiction maybe exercised. The definition of genocide is identical to that contained in the Genocide Convention. The definition of crimes against humanity does not require any nexus between the commission of such crimes and an armed conflict (this accords with existing international law). A detailed definition of war crimes is provided, enabling the Court to exercise jurisdiction over such crimes whether committed in the course of an international or internal armed conflict.“

The ICC was established as a permanent and independent international body that would look into the crimes committed against humanity. In this article, we shall look at the significance and the supposed drawbacks of the ICC. Furthermore, we shall look at the one significant problem that is extended against the ICC, with regards to it being a western court that only looks into the matters concerning Africa. Adding to this, the essay shall also consider the recent advancement made by the ICC, regarding its initial investigations into the crimes committed in Afghanistan and Palestine. Adding to this, the ICC has also entered into the arena of crimes against the destruction of cultural heritage and environmental crimes. The aim of the essay is to critically analyse the ICC, especially with respect to the previous ad hoc tribunals set up by the United Nations Security Council, along with identifying its limitations and importance equally.

Significance and Problems of the International Criminal Court

The significance of the ICC can only be noted under the light of other ad hoc tribunals which were set up by the United Nations after the 1990s. Firstly, the ICC, which is a treaty-based body, works in cooperation with the respective state governments where the crime was committed. This in turn includes the building of accountability within the state because of the internationalization of the crime. However, the same assumes that there would be unhindered cooperation from the state, which has proved to be contrary in many cases that the ICC has handled to date.

Secondly, the ICC is a global body, which has a global mandate (with the exceptions of a few countries). The UN Security Council has the ability to refer any case to the ICC, and thus, it can be noted that the jurisdiction of the ICC is not restricted in this case. However, it must also be noted, as in the case of Syria (discussed in detail later in the essay), that the same can act as an obstruction too.

Thirdly, the ICC is a permanent body with an infinite reach in the future. Daniel D. Ntanda Nsereko aptly sums up this as, “The good thing about the Court’s potential perpetual existence is that it serves to put on permanent notice all would-be tyrants and transgressors of international humanitarian law that there is in The Hague a prosecutor who is watching and monitoring their actions and who has power to bring them to justice when it is appropriate to do so; there are also judges ever at the ready to try them and, if they find them guilty, to punish them”.

Fourthly, the ICC respects the voices of both the victims and the accused. Other ad hoc tribunals such as the ICTR and the ICTY, under the procedures, listen to the charges against the accused or suspect without his/her presence. Article 61 of the Rome Statute mentions that “Subject to the provisions of paragraph 2, within a reasonable time after the person’s surrender or voluntary appearance before the Court, the Pre-Trial Chamber shall hold a hearing to confirm the charges on which the Prosecutor intends to seek trial. The hearing shall be held in the presence of the Prosecutor and the person charged, as well as his or her counsel.” Furthermore, the Rome Statute also calls for an unbiased investigation into the matter, which is defined in article 54 (1), which orders the prosecutor to “investigate incriminating and exonerating circumstances equally”. Furthermore, Article 67 (2) states that, “In addition to any other disclosure provided for in this Statute, the Prosecutor shall, as soon as practicable, disclose to the defence evidence in the Prosecutor’s possession or control which he or she believes shows or tends to show the innocence of the accused, or to mitigate the guilt of the accused, or which may affect the credibility of prosecution evidence”. Finally, the Rome Statute bestows upon the ICC, the power to punish the individual charged with the crime, which was absent in the ad hoc tribunals.

The ICC has already started to show its significance on a global platform despite its drawbacks. According to Luis Moreno Ocampo, the Prosecutor, “Deterrence has started to show its effect as in the case of Cote d’voire, where the prospect of prosecution of those using hate speech is deemed to have kept the main actors under some level of control; in Colombia, legislation and proceedings against paramilitary were influenced by the Rome [Statute] provisions; … arrest warrants have brought parties to the negotiating table; … exposing the criminals and their horrendous crimes has contributed to weaken the support they were enjoying”.

Drawbacks of the ICC: a case study of ICC in Africa

After the creation of several ad hoc international tribunals for crimes against humanity, the adoption of the Rome Statute was considered to be a great victory. However, since its inception, it must be noted that out of the 25 cases on which the ICC has given due consideration, the majority of them are against African countries, which in turn has projected an image of ICC as a western institution that can merely offer retributive and selective justice. In March 2009, the ICC issued an arrest warrant against Omar Al-Bashir, the Sudanese President, which is considered as the tipping point, after which ICC was perceived as a court for Africa by the world at large. As Jean Ping states, “we think there is a problem with the ICC targeting only Africans, as if Africa has been a place to experiment with their ideas.” Adding to this, it is also important to note that out of the 53 African states in the African Union, 30 states have ratified the Rome Statute, thereby being the largest regional group to have supported the formation of the ICC.

One of the prime factors for a large number of countries from the African Union ratifying the Rome Statute was that the continent in particular has seen some grave atrocities being committed. The 1994 Rwandan genocide which is considered to be amongst the most horrible event to have occurred in the continent, the African states came together for the establishment of an independent international court which would have the capacity to punish those responsible for such heinous crimes. Thus, there is strong link between African nations and the ICC. Philipp Kastner while scathingly attacking the ICC as a western institution which can only notice the crimes committed against humanity in the African countries, also points to the fact that, “although the ICC is not a court exclusively constructed for Africa but an inclusive institution aspiring universal ratification, the proportionally strong support of African states for the ICC combined with fundamental legal principles on which the Rome Statute is based make the referral of situations arising from the continent to the ICC more likely.” Adding to this, there are two reasons in particular why the ICC has focused its larger attention on the African states – temporal limitation and principle of complementarity.

The Rome Statute was ratified on 1st July 2002, and according to article 11(1), genocidal acts, war crimes and crimes against humanity can only be addressed by the ICC post the date of ratification. Since the date of ratification, indeed there have been various crimes committed against humanity throughout the world (like Syria, Afghanistan and Palestine to name a few), however, the jurisdictional requirements coupled with the principle of complementarity, restrict the ICC to look into several matters of concern. It is a matter of fact that a significant number of matters in Africa came under the limelight of the ICC. But there arises a problem due to the temporal limitation of the ICC, as posited by Philipp Kastner, “the temporal limitation to the jurisdiction makes the Court focus on present conflicts and not on crimes committed in a distant past. As a result, an ICC involvement is particularly sensitive and often controversial. It has the potential to contribute to ending grave crimes but also bears the danger of prolonging a conflict by adding to the insecurity of the warring parties.” However, it may also be noted, as in the case of Uganda, for which the ICC can look into the crimes committed by the leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The ICC may “still be legally relevant as evidence of a pattern of conduct…” with respect to the crimes committed by the LRA since 1980s.

Adding to this limitation is the principle of complementarity. The preamble of the Rome Statute states that “it is the duty of every State to exercise its criminal jurisdiction over those responsible for international crimes”. The ICC thus faces restrictions with respect to cases where a genuine investigation is underway within the state. Article 17 (1) (a) of the Rome Statute states that a case cannot be put on trial by the ICC if, “the case is being investigated or prosecuted by a State which has jurisdiction over it, unless the State is unwilling or genuinely unable to carry out the investigation or prosecution.” The term ‘unwillingness’ is of key importance, which is defined in Article 17 (2) as, “shielding a person concerned from criminal responsibility for crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court”, or an “unidentified delay in the proceedings”, or “the proceedings were not or are not being conducted independently or impartially.” The term ‘inability’ is defined in article 17 (3) as, “total or substantial collapse or unavailability of its national judicial system, the State is unable to obtain the accused or the necessary evidence and testimony or otherwise unable to carry out its proceedings.”

A summation of Article 17, in short, directs to the high threshold of admissibility of cases in the ICC. Bangamwabo (2009) aptly states, “there is no doubt that African national legal systems are inherently weak and, thus not well-balanced enough to prosecute serious international crimes and grave breaches of international humanitarian law.” The situation persisting in Kenya, Darfur, Central African Republic, DRC, and Uganda exemplify the said situation and call for an immediate intervention by the ICC. As stated by Jalloh (2009), “African states are likely to be the frequent users, or ‘repeat customers’, of the Court because of a relatively higher prevalence of conflicts and serious human rights violation and a general lack of credible legal systems to address them.”

Hence, given the two reasons, African countries become a fertile ground for the ICC, whereas, it is difficult for the ICC to stretch its jurisdiction beyond the signatory countries. Thus, neither is it a coincidence nor a planned attempt by the ICC to target the African countries, as can be noted in its recent investigation in Palestine and Afghanistan (as discussed in the next part of this article).

Expectations with the ICC: Beyond Africa, Environmental and Cultural Heritage Destruction

When the ICC was formed after the ratification of the Rome Statute, it was a generally accepted notion that more accountability for heinous crimes committed against humanity will be accounted for internationally by an independent court. The charges levelled against the ICC for only focussing on the African countries have been dealt with in the previous section. In this section, we shall look at the inherent potential of the ICC, with respect to its ongoing investigation in Palestine and Afghanistan. We shall also look at the limitation of the ICC in regards to the crimes being committed in Syria, where ICC has no jurisdiction and neither is the UN Security Council allowing the ICC to look into the matters. Furthermore, ICC’s recent encounter with crimes committed in relation to the destruction of cultural heritage and environment, further throws light on the importance of the ICC as an international and independent court for justice.

On 1st January 2015, the Palestinian Government ratified the Rome Statute under article 12 (3), thereby accepting the ICC’s jurisdiction over its territory to look into the crimes being committed “in the occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem, since June 13, 2014.” In Gaza, after the Six-Day War of 1967, Israel had taken control over the region, while in September of 2005, Israel unilaterally withdrew from the region. However, it has been alleged that Israel still holds control over the region, especially after 2006, with Hamas’ victory in the elections, which saw periods of hostilities between Hamas and Israel, along with other armed Palestinian groups who are operating in the region. However, in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, after the war of 1967, Israel took control of the region by extending its laws, administration and jurisdiction. Several peace talks were held between the authorities of Palestine and Israel, however, they failed to reach a consensus on the issue.

The preliminary investigations conducted by the ICC acknowledged a high number of casualties, including both Palestinian and Israeli civilians, that took place during the 51-day conflict, which began on 7th July 2014 and lasted till 26th August 2014. The report while highlighting the atrocities committed against children states that, “more than 500 children were killed, and more than 3,000 Palestinian children and around 270 Israeli children were wounded during the conflict. In addition, several instances of child recruitment by Palestinian armed groups have been reported.” The report further goes on to record several unlawful acts committed by the members of Palestinian armed groups and the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) equally.

Furthermore, in the region of West Bank and East Jerusalem, the report states that “the Israeli government reportedly destroyed 531 Palestinian-owned structures in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, allegedly displacing 688 people, according to figures published by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs” and that, “Since the beginning of October 2015, there has been an escalation of tensions and violence in Israel and Palestine, including alleged violent attacks by Palestinian assailants against Israelis and others, resulting in killings and serious injuries, as well as alleged unlawful killings and/or excessive use of force by Israeli forces against Palestinians.”

The Office of the Prosecutor took steps to identify and report the gross violations in the region as well as spread awareness about the importance of the ICC as an independent international court. The preliminary report also states treats and “other apparent acts of intimidation and interference” faced in the region. The report makes the conclusion that “The Office is continuing to engage in a thorough factual and legal assessment of the information available, in order to establish whether there is a reasonable basis to proceed with an investigation. In this context, in accordance with its policy on preliminary examinations, the Office will assess information on potentially relevant national proceedings, as necessary and appropriate. Any alleged crimes occurring in the future in the context of the same situation could also be included in the Office’s analysis”, which can be a potential way to solve the unending crisis between Israel and Palestine. It is also important to note that the ICC, as an unbiased organization, saw the violations committed by both the parties and not just one. Therefore, one can note that ICC is an important panel to look into the crimes committed against humanity.

In reference to Afghanistan, the Office of the Prosecutor received over 112 communications on or before 2015 which were in compliance with article 15 of the Rome Statute, where article 15 (1) states that the “prosecutor may initiate investigation proprio motu on the basis of information on crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court.” Afghanistan had submitted its instrument of ratification on 10th February 2003, and thus, the ICC has jurisdiction over the crimes committed after the mentioned date.

The 2016 ICC report sums the situation in Afghanistan as, “The situation in Afghanistan is usually considered as an armed conflict of a non-international character between the Afghan Government, supported by the ISAF and US forces on the one hand (pro-government forces), and non-state armed groups, particularly the Taliban, on the other (anti-government groups). The participation of international forces does not change the non-international character of the conflict since these forces became involved in support of the Afghan Transitional Administration established on 19 June 2002.” In the case of Afghanistan, like that of Palestine, the ICC has taken all the perpetrators of crime in the conflict and has decided to charge the Taliban, the Afghan government forces and the US military forces which were deployed in Afghanistan.

Thus, the ICC is expected to take actions beyond the African countries and has time and again, during its short term, proved to be a truly independent international criminal court for the justice of people who have suffered gross violations. However, problems of jurisdiction still impedes justice as can be noted in the case of Syria, which has been particularly in limelight especially in the international media.

The Syria and the International Criminal Court Q&A, conducted by the Human Rights Watch in September 2013, it was duly noted that with Syria not being a member state of the Rome Statute, ICC cannot take actions against the crimes being committed there, whereas the Syrian National Coalition has granted support for the intervention of the ICC. However, a Security Council referral would give the ICC, the necessary jurisdiction to look into the matters. For this, six UN Security Council Members, which include, South Korea, Australia, Argentina, Luxembourg, the UK and France have expressed their support. However, China, the US, and Russia have not expressed their support, and it must be noted that all these three countries currently have the power to veto any decision.

Adding to this, the ICC has also looked into matters concerning the destruction of cultural heritage sites, which was reflected in its decision against Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi who was charged with destroying sites related to cultural heritage in Timbuktu. Here the ICC saw cultural destruction as a war crime. The Judge, Pangalangan, while explaining the grievous nature of the crime committed, exclaimed that, “the heart of Mali’s cultural heritage were of great importance to people of Timbuktu”, further adding that, “their destruction does not just affect the direct victims of the crimes, but people throughout Mali and the international community.”

The ICC has also recently decided on widening its horizons to meet environmental crimes, given the climate change destruction prospects in the world. The ICC in September 2016 claimed that “it would start focusing on crimes linked to environmental destruction, the illegal exploitation of natural resources and unlawful dispossession of land in a move hailed by land rights activists”. This act, in particular, not just marks the importance of the ICC on the global stage, but also hints at the fact that there has been an increasing recognition against environmental crimes globally, which is the need of the hour.

Conclusion

Unlike the other ad hoc tribunals set up by the UNSC, the ICC has evolved to be a permanent and impartial tribunal for solving crimes against humanity. There are many advantages pertaining to the ICC, especially due to its impartial and independent character, which sets it apart from all the tribunals which were set up by the United Nations.

With its recent expansion to addressing the crimes against cultural heritage and environmental crimes, alongside the extension of its domain beyond African countries, the ICC has truly lived up to the expectation on which the tribunal was formed. It is hopeful that after analysing the success of the ICC, other countries shall also ratify the Rome Statute in order to expand the tribunal’s jurisdiction, thereby absolving the ICC of its limitations.

*Ifra Jan is an Additional Spokesperson of the J&K National Conference.

**Karmanye Thadani is the President of the Citizens’ Foundation for Policy Solutions (CFPS), a public policy and foreign policy thinktank based in New Delhi.

P.S. The views expressed in this article by Ifra and Karmanye are in their personal capacities.