The arbitral tribunal of Prof. Piero Bernardini (President), Mr. Gary Born, Judge Prof. James Crawford in Philip Morris v. Oriental Republic of Uruguay (ICSID Case No. Arb/10/7) has finally ruled on merits, dismissing the claims presented by Philip Morris (“PM”) and awarding costs to the tune of US$ 7 million to Uruguay. This award will have huge implications on the tobacco industry and countries like India who are seeking to regulate tobacco consumption through plain packaging measures as it was reportedly the first time a tobacco group had taken on a country for its anti-tobacco laws. Many are characterising Uruguay’s victory as something that will change the world. In this post, I will only focus on the claim of expropriation and the other claims of denial of justice, fair and equitable treatment and impairment of use and enjoyment of investments will be discussed in subsequent posts.

Factual Background

PM had challenged several tobacco-control measures introduced by Uruguayan Government between 2008-2009.

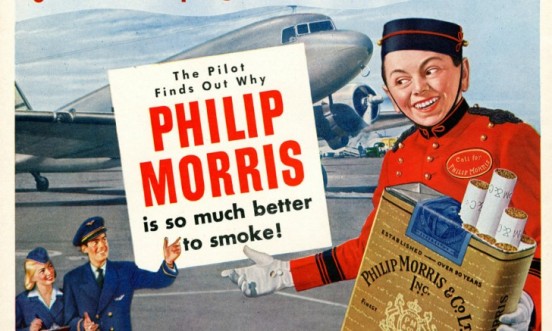

This was also preceded by several other measures, two of which were the Presidential Decree 171/005 and Decree 36/005 which mandated that the health warnings in the packages of tobacco products should not only occupy 50% of the total display areas, but that they shall also be periodically rotated, and include images and/or pictograms. It also prohibited the use of terms such as such as “low tar,” “light,” or “mild” on tobacco product. Consequently, the companies renamed their brand variants to comply with these decrees. For instance- Marlboro light was renamed as Marlboro Gold. However, it was noticed that the companies managed to avoid compliance with these regulations and the effect was not satisfactory. Thus, the alternative of plain packaging was suggested which finally culminated into the measures challenged by PM.

The measures challenged by PM included- a) Single Presentation Requirement implemented through Ordinance 514 dated 18 August 2008 (“SPR”), and b) 80/80 Regulation implemented through the Presidential Decree No. 287/009 dated 15 June 2009 (“80/80 Regulation”). By the SPR requirement, the tobacco companies were precluded from marketing more than one variant of cigarette per brand family. As a result of this, the tobacco companies had to withdraw all but one variant of cigarettes per brand from the market. For instance, before the enactment of SPR regulation, many variants of “Marlboro” brand cigarettes were sold in the market (such as Marlboro Gold, Marlboro Red, Marlboro Blue, Marlboro Green (Fresh Mint)). However, after the enactment of SPR regulation, PM (operating through Abal Hermanos S.A. in Uruguay) had to stop selling all but one of these product variants. PM alleged that this substantially impacted the value of the company, thus giving rise to violations of Uruguay’s obligations under the Switzerland-Uruguay BIT (“BIT”). By the 80/80 regulation, the Government introduced, what is often termed as plain packaging, and imposed an increase in the size of prescribed health warnings on the front and back of the cigarette packages from 50% to 80%, thus leaving only 20% of the cigarette pack for trademarks, logos and other information. PM alleged that that this caused deprivation of its intellectual property rights (right to use its legally protected trademarks), thus reducing the value of investment.

PM alleged breaches of Uruguay’s following obligations under the BIT-

- Articles 3(1) (impairment of use and enjoyment of investments)

- Article 3(2) (fair and equitable treatment and denial of justice)

- Article 5 (expropriation)

- Article 11 (observance of commitments)

Claim of Expropriation under Article 5 of the BIT

- The Legal Standard

PM argued that a violation of expropriation does not depend on a finding that PM was deprived of the economic benefit of its investment in its entirety. In other words, the threshold for a finding of expropriation is ‘substantial deprivation’ and not ‘complete deprivation’. It also contended that the exception of ‘public benefit’ was not a valid exception but instead one of the several prerequisites for an expropriation to be considered consistent with the BIT. For this contention, PM pointed out the absence of any such provision in the BIT providing for “carve-outs, exceptions or saving presumptions for public health or other regulatory actions” which stood in clear contrast with other BITs such as the Uruguay-U.S. BIT which contain such provisions.

In response, Uruguay contended that the tribunal first had to determine whether the measures were expropriatory in character. This determination depended on the nature of Uruguay’s action. According to Uruguay, “interference with foreign property in the valid exercise of police power is not considered expropriation and does not give rise to compensation”. It further argued that a claim for indirect expropriation requires a demonstration of an economic impact so severe that assets at issue are rendered virtually without value and mere negative impact was not sufficient. Uruguay relied on the awards made in Archer Daniel v. Mexico, LG&E v. Argentina, CMS v. Argentina and Encana v. Ecuador to argue that if “sufficiently positive” value remained, there would be no expropriation. I found a statement made by Uruguay in its counter memorial of particular interest: “if States were held liable for expropriation every time a regulation had an adverse impact, effective governance would be rendered impossible.”

The tribunal ruled that a state’s measure should amount to “substantial deprivation” of investment’s value and the determinative factors in this regard are “the intensity and duration of the economic deprivation suffered by the investor as a result of such measures.”

- The Claim

PM alleged that by imposing SPR and 80/80 regulation, Uruguay effectively banned seven of its thirteen variants and substantially diminished the value of the remaining ones, thus expropriating its brand assets, including the intellectual property and goodwill associated with each of the brand variants. It was further alleged by PM that by forcing to choose between maintaining its market share and maintaining its historical price, Uruguay’s measures destroyed PM’s brand equity and substantially affected the Claimants’ profits and revenues as smokers were now less willing to pay premium prices for the Claimants’ products. In response to the fact that PM’s business was still profitable, PM contended that each brand was an individual investment in its own right, thus the discontinuance of each brand variant constituted expropriation.

On the other hand, Uruguay argued that the effect of these measures did not amount to expropriation as PM’s business was still profitable and that the analysis of indirect expropriation must focus on the investment as a whole, globally and not on its discrete parts.

Against this claim of indirect expropriation, Uruguay raised two defenses- firstly, the police powers doctrine, and secondly, PM’s lack of property rights over the trademarks.

Uruguay argued that the police power doctrine was a fundamental rule of customary international law and must be applied to interpret Article 5 of the BIT, in accordance with Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Moreover, Article 2(1) of the BIT explicitly recognized this doctrine by allowing the contracting States to refuse to admit investments “for reasons of public security and order, public health or morality.” Hence, a bona fide and non-discriminatory exercise of a State’s sovereign police power to protect health or welfare does not constitute an expropriation as a matter of law.

For the defence of PM’s lack of property rights, Uruguay contended that marks being used in all brand variants were not the same as any of the trademarks originally registered, and therefore they should have been separately registered. For instance- the use of mark Marlboro Gold could not have been protected by the registration of Marlboro Light. Accordingly, there was no valid expropriation claim as PM could not have claimed protection over these marks.

It further argued that Uruguayan intellectual property law did not afford trademark registrants an affirmative right to use their marks. Instead, what was conferred was only the negative right to prevent others from using their trademarks. Hence, the mere act of registering a trademark could not have been used as a shield against government regulatory action that restricted the use of such marks, or the products with which they were associated. Thus essential precondition of expropriation- presence of extant legal rights was missing.

While addressing the above-mentioned two defenses, PM argued that:

- State police power was not a valid defence for expropriation under the customary international law.

- The government actions were not “designed and applied to achieve” reduced tobacco consumption.

- This exception is inapplicable where the government’s actions conflict with specific commitments to investors.

- Respondent had not conducted a “serious, objective and scientific” assessment of whether the measures were justified. Moreover, the measures had been ineffective in practice and were not proportional to the public interest given the severe harm they inflict.

- The trademarks were validly registered before Uruguay’s National Directorate of Industrial Property and thus benefit from legal protection.

- The disputed marks maintained “the distinctive characteristic” of the registered trademarks, and were therefore covered by the same original registration regardless of they not being identical. The use of descriptors such as “light,” “mild flavour,” or “milds” are not distinctive, but instead are common in the tobacco industry and are non-essential elements. Thus, their absence on the branded packaging was without any effect.

- The Uruguayan trademark law incorporates international law and thus also encompasses the right to use the trademarks. Moreover, the Uruguayan property law applies to intellectual property and protects the right to use intellectual property.

- Tribunal’s analysis of the Claim

In light of its other findings, the Tribunal did not consider it necessary to reach a definitive conclusion on the question of the PM’s ownership of the banned trademarks. However, it assumed, without deciding, that the trademarks continued to be protected under the Uruguay Trademark Law.

While the parties had advanced arguments on right to use v. right to protect, the tribunal viewed the question as one of absolute use v. exclusive use. It observed that that the ownership of a trademark does grant a right to use it, albeit, only in certain circumstances. This right to use exists vis-à-vis other persons and is a relative right rather than being an exclusive right, but a relative one. In other words, the tribunal ruled that right to use trademarks was not an absolute right that can be asserted against the State in the capacity of a regulator but only an exclusive right to exclude third parties from the market, subject to the State’s regulatory power. In what would be of far-reaching consequences, the tribunal made an observation that in industries like tobacco, the presentation to the market needs to be stringently controlled without being prohibited entirely, and whether this is so must be a matter for governmental decision in each case.

The tribunal rejected Uruguay’s contention that the absence of any right to use also meant that trademark rights were not property rights under Uruguayan law as it must be assumed that trademarks are registered to be put to use, even if a trademark registration may sometime only serve the purpose of excluding third parties from its use. Hence, PM’s rights over its trademarks were capable of being expropriated.

However, the tribunal did not even find a prima facie case of indirect expropriation. This was for the reason that the Marlboro brand and other distinctive elements continued to appear on cigarette packets in Uruguay. The tribunal refused to accept that the limitation of 20% of the space had a substantial effect on PM’s business since this limitation was imposed by the law on the modalities of use of the relevant trademarks.

For the purpose of determining whether a claim of indirect expropriation may relate to identifiable distinct assets comprising the investment or is to be determined considering the investment as a whole, the tribunal adopted a ‘facts and circumstances’ approach, i.e. the answer largely depends on the facts of the individual case. The tribunal observed that PM, in order to mitigate the effect of measures, resorted to counter measures involving its business as a whole. For instance, prices were changed across the portfolio. Since the measures affected PM’s activities in entirety, the tribunal ruled that PM’s business had to be considered as a whole.

The claim was also rejected on the ground that the standard of ‘substantial deprivation’ was not fulfilled as there was merely a partial loss of profits and no such ‘substantial deprivation’ was caused to the value, use or enjoyment of PM’s investments. Thus, this award is another addition to the line of awards that have recognized what is often referred as the ‘effects doctrine’ in cases of indirect expropriation.

On the issue of police power, the tribunal revisited the jurisprudence and concluded that public health was a valid manifestation of police power. In this regard, it held: “protecting public health has since long been recognized as an essential manifestation of the State’s police power, as indicated also by Article 2(1) of the BIT which permits contracting States to refuse to admit investments “for reasons of public security and order, public health and morality.””

Contrary to what PM alleged, the tribunal found that Uruguay’s measures were bona fide for the purpose of protecting the public welfare and were non-discriminatory and proportionate. The tribunal held that a demonstration that the incidence of smoking in Uruguay had declined, notably among young smokers and that these were public health measures which were directed to the end of tobacco control and were capable of contributing to its achievement, was enough for defeating the claim of expropriation.

For these reasons, the claim regarding expropriation was rejected.

Hey how are you?

LikeLike