Introduction

On 27 February 1940, the Look magazine published the comic strip, “How Superman Would End the War” (Comic Strip). The creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, co-creator of Superman, published a short story. In this story, Superman zooms off to Germany and Stalin, where he picks up Hitler and Stalin, by the scruff of his neck.; he takes the two dictators to Geneva, Switzerland, where he delivers them to the League of Nations’ World Court for trial. The League of Nations was first proposed by President Woodrow Wilson as part of his Fourteen Points plan for equitable peace in Europe. It was dissolved after the second World War, in 1946, to make room for the United Nations. Consequently, the League of Nations’ World Court in Geneva was succeeded by the United Nations’ International Court of Justice/ World Court in The Hague.

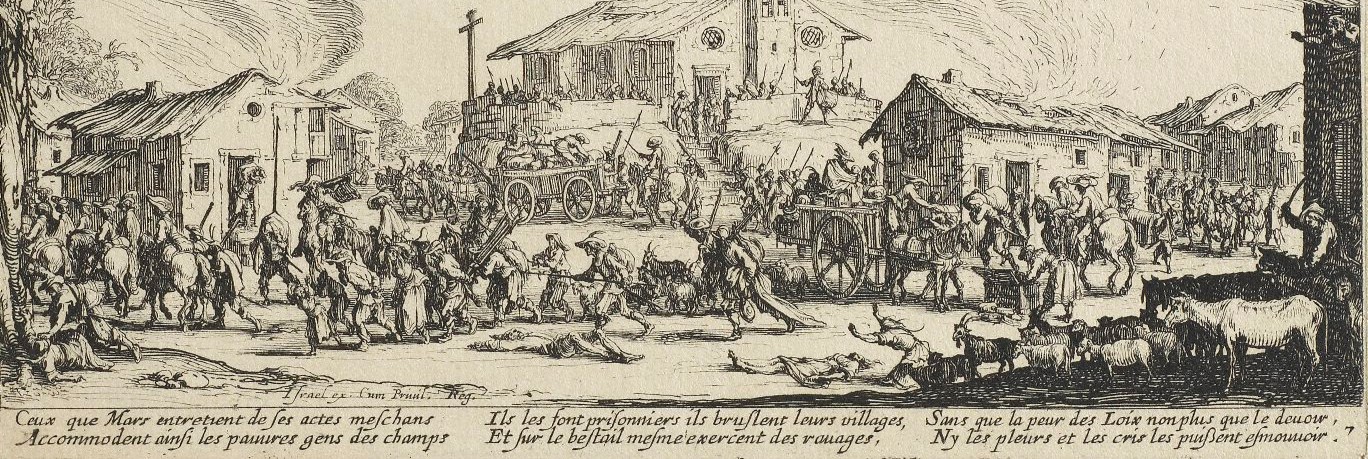

It is important to highlight that “How Superman Would End the War” is a fragment of the American imagination of war, uprising, and emancipation. It remains a vestige of time and imagination of a super-heroic/ hegemonic intervention against dictators. In other words, Superman’s intervention was based on nationalism or patriotism. In the recent past, the United States has interfered in domestic politics through igniting and continuing civil wars and unrest. This trend began in the 1970s, at the height of the cold war between the United States and the Soviet Union, when the Nixon Administration started shipping weapons to counter Soviet expansion. The policy was called the Nixon Doctrine , the aim of which was to substitute American weapons for American boots- send weapons instead of troops to their lands. While in the Comic Strip, Superman submits the dictators to the League of Nations for trial in the Hague, in practice, American intervention has adopted other measures.

On Superman and Imagination

Superman, one can safely assume, would allow domineering characters to dictate. It can also be argued that, similar to our modern internationalist principles, the underlying motivation would be to seek order in our institutions that shall neither oppress nor bequeath any precedence of oppression. Superman would hold dearly ambition and greed as carriages of inspiration and aspiration to save humanity from the mindless stagnation of the accursed Victorian snobbery and the verge of ruin it carries. Dictators, Superman would argue, must be curbed by social institutions. But when our institutions are not adequate for the purpose, the whole population must be made to understand and accept the responsibility of politics around them. Only then can the values of dictators operate for the benefit of the race without endangering the race in the process. To this end it is valuable to quote the Preface to Geneva: “The rule of vast commonwealths is beyond the political capacity of mankind at its best”.

Hegemonic International Law (HIL)

In Geneva, the dictators are disposed of along with all the rest of the politically helpless characters. Despite the process, what accrues from it is the trust in the hope of a future evolutionary leap for the development of homo sapiens into a competent political animal. At the center of this, one may refer to Yuval Harrari’s colossus, Sapiens, wherein he argues that homo sapiens are the most successful species of human beings, supplanting rivals such as Neanderthals, because of its ability to believe in shared fictions. Hence, Geneva is no paean to dictators. As an academic study of a framework, HIL severely undervalues the formal and de facto equality of states, replacing pacts between equals grounded in reciprocity, with patron-client relationships in which clients pledge loyalty to the hegemon in exchange for security or economic security. In this real-world application of the Comic Strip, state(s) act like Superman, where hegemon(s) promotes, by word and deed, new rules of international law. These can either be acts of realization or detente but are ingrained in treaty and custom. Such a hegemon is generally averse to limiting its scope of action via treaty; avoids being constrained by those treaties to which it has adhered; and disregards, when inconvenient, customary international law, confident that its breach will be hailed as a new rule.

Substantively, HIL is characterized by indeterminate rules whose vagueness benefits primarily (if not solely) the hegemon. As noted earlier, recurrent projections of military force and interventions in the internal affairs of other nations are character traits of hegemon states. While Superman operates from a benign perspective, the United States has used international organizations to magnify its authority by a judicious combination of voting power and leadership. Placing both subjects of this note side-by-side one realizes that forms and expressions of hegemony are capable of winning praise or condemnation from all points on the political spectrum.

Global HIL results from the privileged position accorded to the hegemon under the existing rules and institutions of international law. Diverse lessons are to be drawn from examples of global HIL. The first is that, from a policy perspective, not all forms of hegemony are bad or equally so. Actions of the Security Council (Council) for counterterrorism efforts respond to the international community’s continuing inability to agree on a single global definition of the crime of terrorism, as well as the piecemeal, incomplete nature of the existing counterterrorism conventions. The affirmation of self-defense measure by UNSC Resolution 1373, adopted in the backdrop of the 9/11 attacks, avoids unproductive debates in the context of a situation where the United States was bound to respond unilaterally. Similarly, the allowance of continuous intervention by the United States in Iraq on account of UNSC Resolution 1483, in what would normally be considered to fall under a state’s domestic jurisdiction, can otherwise be justified as a vital part of rebuilding a stable and viable Iraq and, similar to the USNC Resolution 687, could be considered ‘necessary’ for peace restoration in Iraq. None of the aforesaid UNSC resolutions are manifestly illegitimate in a political sense, as all of them were adopted unanimously or with near consensus.

The United States cannot and should not be barred from securing the Council’s cooperation in the pursuit of the common good and the collective can hardly be blamed for using the Council to avoid the potentially greater harm of unilateral HIL. Although global HIL is characterized by demonstrable power disparity, it may preclude the exercise of even greater power disparities. As defenders of the Council-generated ad hoc war crimes tribunals would be the first to argue, it may sometimes be necessary for Council members to use their exclusive legislative capacity to short-circuit arduous international treaty negotiations. But the troubling features and risks posed by Council-generated HIL lead to a second lesson: it is not enough to urge the hegemon to use the United Nations. Those concerned about the risks of hegemony need to worry about how the hegemon uses the Organization, especially the Council. The risks that unilateral HIL poses to international law and its formal principles, such as sovereign equality, are grave, but they are obvious. The comparable challenges posed by global HIL, potentially no less serious, are unclear and novel. When acting with the Council, the hegemon, like Superman, can do almost anything. While still appearing to be acting consistently with the Charter’s and moral principles enshrined therein. However, if the Council and the hegemon decide jointly to revise the rules relating to due process, rights of individuals, defensive force, the rights of occupiers, or the jurisdiction of the ICC, the Council’s legitimacy may be undermined.

Conclusion

Continuity and similarities between superheroes and countries have intertwined over the years; with one character making a change in the world meant that those changes would resonate with other characters and the world they inhabit, thereby they inhabiting an increasingly unrecognizable world. While such mechanisms may be essential for securing continued multilateral cooperation in future, whenever the hegemon and others require it so, the Council will retain its legitimacy as a body for collective global action if it is perceived to be acting in accordance with the essence by and for which it was formulated. Recognizing the phenomenon of global HIL also makes one more aware of taking cautionary steps for reformation that need to be made to make sure the Council is not subject to even more hegemonic dominance.