By Rakesh Roshan*

On 1st July 2017, the International Criminal Court completed 15 years. While there are 24 cases that have been brought before the Court, it has only managed to convict 4 individuals in all these years, but it is hoped that it carries to deliver universal justice in an unprecedented manner.

The International Criminal Court is the most ambitious, treaty-based international organisation established through the Rome statue. It is mandated to prosecute grave criminals, nevertheless them being powerful leaders and military commanders, who have committed crimes which concern the international community and promise to deliver universal justice to the victims. UN General Secretary Kofi Annan stated:

“In the prospect of an international criminal court lies the promise of universal justice. That is the simple and soaring hope of this vision. We are close to its realization. We will do our part to see it through till the end. We ask you … to do yours in our struggle to ensure that no ruler, no State, no junta and no army anywhere can abuse human rights with impunity. Only then will the innocents of distant wars and conflicts know that they, too, may sleep under the cover of justice; that they, too, have rights, and that those who violate those rights will be punished.”

His Excellency recently made an impassioned call to stand by the ICC when some African nations intended to quit the court.

While 124 state parties have adopted the Rome statue which shows worldwide commitment to promoting universality, however, States like USA, Russia, China and India being not a party to it is a discouraging trend to the Court’s global support. The ICC President Judge Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi stated:

“there is a widespread expectations that atrocious crimes cannot go unpunished. The court must fulfill its mandate, but it cannot meet these expectations alone. It relies heavily on the cooperation of states and organizations.”

The preamble of the Rome Statute states that “most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole must not go unpunished as such grave crimes threaten the peace, security and well-being of the world.” Under Article 5, the court has jurisdiction over the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression. The definition of a Crime of Aggression was adopted through amending the Rome Statute at the first Review Conference of the Statute in Kampala, Uganda, in 2010.

The Court may exercise its jurisdiction on such crimes when [a] a State party is referred to the Prosecutor in accordance with Article 14 of the Rome Statute, [b] UN Security Council has referred to the Prosecutor acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, and [c] the Prosecutor initiates investigations proprio motu in accordance with Article 15.

Further, the Prosecutor may admit a case and initiate an investigation if [a] she reasonably believes that such crime is within the territorial jurisdiction of the Court, [b] consistent with complementarity principle, and [c] serve the interests of justice.

The most important and unique inclusion of international justice is the participation of victims in ICC proceedings and present their views and concerns to judges which are absent in the most national courts and ad-hoc tribunals. Moreover, a victim can also claim reparations in the form of restitution, compensation and rehabilitation when the defendant is convicted.

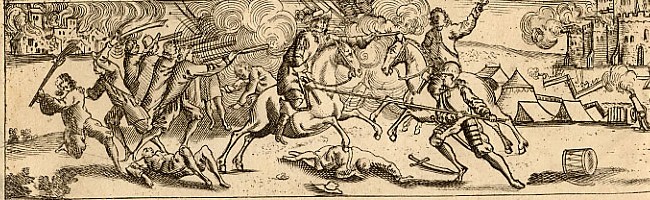

In 1947, the French judge Henri Donnedieu de Vabres on International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg made a proposal to set up a Permanent Criminal Court within the United Nations framework. Nevertheless, Christopher Keith Hall, argues that the inception of the idea was first made by Gustave Moynier one of the founder and presidents of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Although, the tribunal of judges from towns in Alsace, Austria, Germany and Switzerland which tried the case of Peter de Hagenbach in 1474 for murder, rape, perjury, and other crimes in violation of the “law of Gods and humanity” appeared to be the earliest ad hoc tribunal international criminal tribunal.

There is no doubt that the roots of the court can be traced back directly to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia along with a draft statue prepared in 1994 by the International Law Commission. However, they can be differentiated at least on two grounds. The first and most obvious that ICC is a permanent judicial body and second and most importantly, ICTR and ICTY were the subsidiary organs of the Security Council while ICC is legally independent of the UN, thus, it is more self-reliant on decision making.

Nevertheless, it has been accused of racism and biasedness on the grounds that it has lost sight of its apolitical nature and only delivers “selective justice” targeting and not transcending Africans. All of this generated a strong backlash against the Court with the possibility of a mass exodus of African nations. Nevertheless, this has not materialised and ICC is supported by a number of African nations and civil society organisations. Moreover, Professor William Schabas argues in favour of the Court’s convictions of the Africans- “the fact that the Court seems obsessed with African situations does not make it a racist court. If the Court had ignored Africa, it would have been accused of racism too. Charges of racism do not help to understand the Court’s selection of priorities for prosecution. It is focused exclusively on Africa because it is afraid to go elsewhere.” Professor Christine Schwöbel-Patel sees it in the context of neo-colonialism and idealisation of certain kind of victims by the Court.

However, he also pointed to the inherent politicisation of the international justice. According to him, the ICC is found on the myth that Security Council is apolitical. Nevertheless, three of its members (The US, Russian and China) were not compelled by the Court to follow its norms and influence referrals of the Security Council, recently in the case of Syria by the Russia and China. Professor Hans Köchler, argues that the existence of power politics in the Security Council has shackled the idea of impartial justice.

Professor Peter Erlinder, Founding Director of the International Humanitarian Law Institute pointed out another flaw that- “Criminal prosecution of individuals by an international body is the antithesis of national sovereignty and creates a supra-national ‘sovereign’ which was never contemplated in the UN structure.” The other argument against the Court is of cost-ineffectiveness as it has already cost over $ 1 bn for two convictions and is currently sustaining on a grand budget of €145 m.

India and the ICC

India and the ICC have a strenuous relationship since the beginning. India abstained from voting in Rome in 1998. India’s objections lie mainly on three grounds.

First, India believes that UNSC is a political institution and case referral from this can be used as a tool against rest of the world. Thus, it submits, the ICC should be a completely independent body and decision on referral should only be limited to the state parties.

The second ground of objection is on Jurisdiction. India has a two-fold argument. a) the Court must not have a compulsory jurisdiction and rather have the optional jurisdiction which can be exercised on the consent of the states, and b) India opposes the idea of prosecutor’s proprio motu powers on an investigation and is afraid that it can be used for political purpose.

The third and the most important objection is the defeat of India’s proposal to include terrorism as a crime against humanity and in the list of core crimes and to exclude usage of nuclear weapons from the list of war crimes in the ICC Statue. The country took rejection very seriously and thus abstained.

In 2015, India refused to abide by the Resolution 1593 which calls on ‘all States and concerned regional and other international organizations to cooperate fully with the ICC investigation’ who is also not a party to the statue. Sudanese President Al- Bashir who is facing two arrest warrant by the ICC was on the official visit to the country to participate in India-Africa forum. PM Mr. Modi even tweeted a group photo with him. In Prof. Usha Ramnathan’s words, India’s view is a result of cynicism and there is a need to adopt universal vision by the country. Further, she quoted, “peace anywhere requires Justice everywhere.”

An alternative to the Court, proposed by the African leaders is the African Court of Justice and Human Rights. This has been established with a major flaw that it would grant immunity to the head of states and “senior state officials.” Nevertheless, ACJHR has been only ratified by only 9 states and it needs to be ratified by at least 15 states to come into force. Thus, an alternative to the ICC is limited.

Richard Dicker, argues that the ICC’s leadership is learning from earlier mistakes and making changes in important areas. Moreover, David Bosco has new hopes from the Court. Professor Ramesh Thakur urges for a genuine adjudication body with an equal enforcement power. However, the most important question which comes to our mind: Is ICC capable of transcending African boundaries and deliver universal justice against powerful nations too?

In 2016, the ICC Prosecutor authorised to open proprio motu investigation in Georgia on the alleged crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in the context of an international armed conflict.

The most important is an ongoing preliminary examination in Afghanistan on the alleged crimes against humanity and war crimes. The US leaders, US Soldiers and CIA Personnel might be put to trial for the same. A full investigation will lead to many storms in the ICC under the Trump regime as it would be the very first international tribunal to try US nationals.

The next request in the queue to the Court is the Palestinian request to the ICC to investigate crimes committed in Gaza Strip and West Bank by Israel. Further, Ukraine has sought from the Court to investigate on the Russian occupation of Crimea. The office of the prosecutor in her ongoing preliminary examination has found that conflict between Russian Federation and Ukraine was an international armed conflict, thus, it falls under the jurisdiction of the Court.

This is an important opportunity at a crucial time for the Court to prove that it is an effective and impartial transnational body to deliver universal justice. Finally, even symbolically, the ICC as an institution can deter most political leaders and military commanders to commit such heinous crimes which are not acceptable by the international community.

————————————————

*Rakesh Roshan is a student at National Law University, Delhi

Perhaps using the recent (July 7) achievement of establishing a treaty for the prohibition of nuclear weapons as a good model – noticeably absent U.S., Russia, China, and India – nuclear weapons nations and simultaneously non-ICC nations, a similar effort to bring moral pressure for universal ICC jurisdiction could lead to good change for humanity.

Simply reforming or amending the United Nations Charter with a provision that it is mandatory for member states to agree on signing the Rome Statute or membership in the United Nations is denied would certainly change the world for this and future generations. From any perspective, such a reform of the U.N. Charter would in short order end war crimes of aggression for all time, clearly a profoundly worthwhile, transcendent goal no man or woman in their right mind would not happily embrace.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on THE ONENESS of HUMANITY and commented:

Student at National Law University in Dehli Rakesh Roshan’s insightful article discussing the International Criminal Court raises the question of what means are available to convince non-ICC nations United States, Russia, China, India and others to sign the Rome Statute and agree to come under the jurisdiction of the ICC.

Imagine you as a citizen of your town or city are deterred by laws against committing brutal crimes, but that citizens in the town or city next to yours have no similar laws, no deterrence against the same brutal crimes, and that citizens in the town or city next to yours commit brutal (war) crimes – with impunity.

That simple analogy makes clear why universal ICC membership as a goal is possibly the most important challenge facing this generation of humanity on Earth.

World peace is possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] via Transnational Justice Matters: An ICC Overview […]

LikeLike